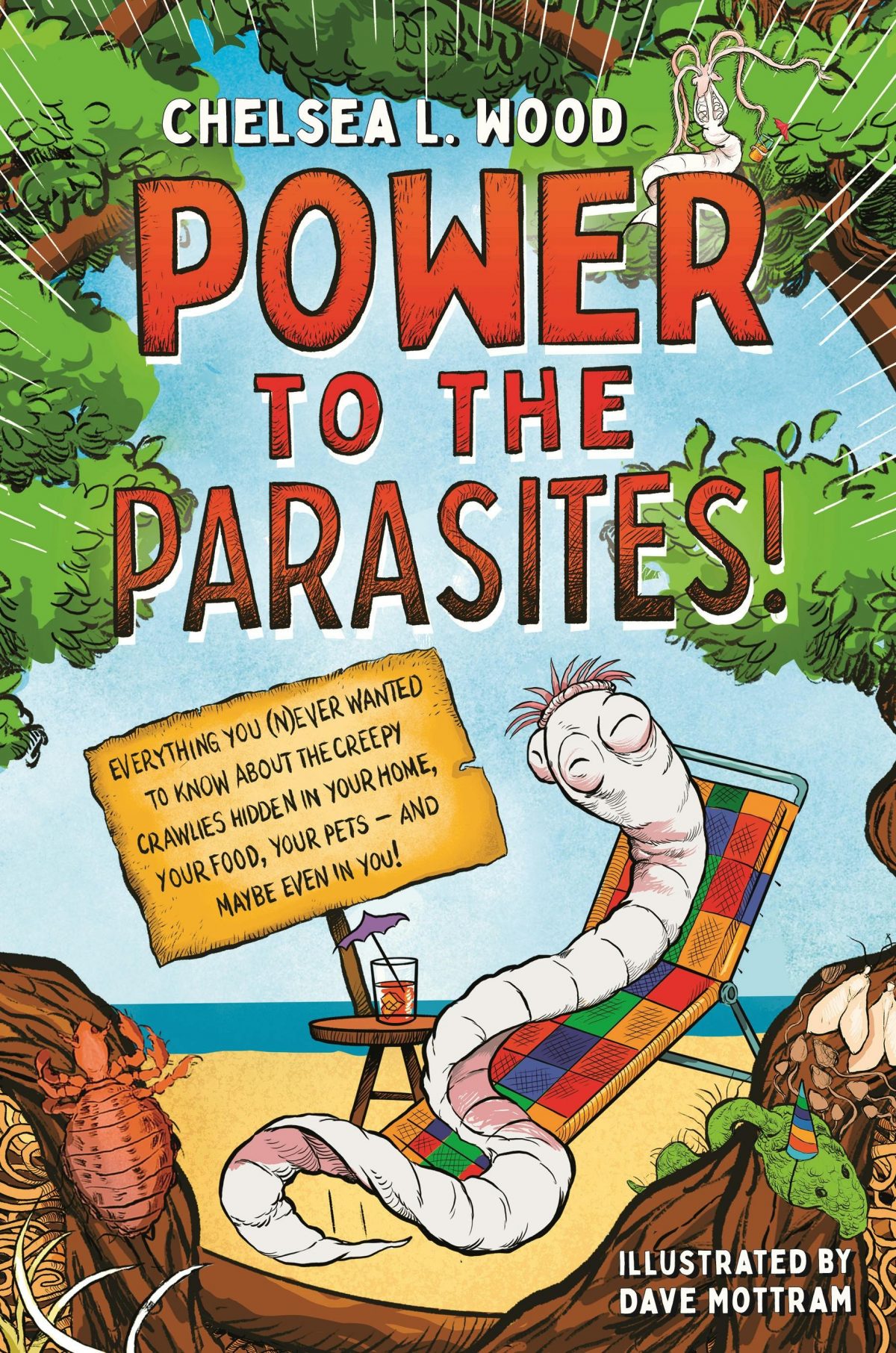

At first glance, I might look like a typical science professor, someone who teaches classes, runs a research lab, and trains graduate students. The reality is so much weirder than that. In Power to the Parasites!, readers get a glimpse of my day-to-day job duties. I am a tour guide, introducing newcomers to the netherworld.

I study parasites: any organism that lives inside or on a host and causes harm to that host, including tapeworms, ticks, viruses, and every blood-sucking, brain-eating, and poop-inhabiting thing in between. Each Autumn, my classroom fills up with fresh-faced undergraduate students who have never once in their 15 years of education heard a peep about parasites. Parasites are so thoroughly excluded from education at all levels that it isn’t uncommon for folks to hold a bachelor’s degree in biology without having had a single lecture on parasitism. This, despite the fact that parasites are, by conservative estimates, 40% of all animal species.

In Power to the Parasites!, I do for elementary-aged readers what my undergraduate courses do for unsuspecting biology majors: I take them by the hand, and show them the most important landmarks in the netherworld of parasites – the good, the bad, the ugly, and the sublime. In the end, there is an important lesson: at first glance, parasites might seem slimy, icky, and dangerous. But when you look closer, you learn: we can’t live without parasites, and even if we could, we might not want to.

Take, as just one example, the single-celled parasite Toxoplasma gondii (Toxo, for short). If you’ve heard of Toxo, it’s probably because you or someone you love have been told by their OB/GYN not to touch any kitty litter boxes during pregnancy. That’s because Toxo replicates in the gut of cats and is dispersed into the world via cat poop. The parasite is present across the globe, and it is extremely dangerous to a developing human fetus, which is why pregnant people the world over need to avoid exposure. Super scary. What’s to like?

Well, when you take a closer look, you start to appreciate that Toxo is more than just a threat to a healthy pregnancy. In fact, Toxo wants nothing at all to do with people. It is passed between cats and rodents. The parasite replicates in the gut of cats and is dispersed into the world in cat poop, where its eggs scatter as the cat turd decomposes, ultimately coming to rest on things that rodents might eat. Once ingested by a rodent, the parasite forms a resistant cyst and waits. It needs to get back into the gut of a cat, and if it waits around for long enough, that might happen; cats love to eat rodents, after all. But Toxo has some tricks up its sleeves. It subtly alters the behavior of infected rodents, which become slower, clumsier, and more reckless than uninfected rodents. Whereas the scent of cat pee sends an uninfected rodent running, it draws infected rodents near. All of these changes make it likelier that the infected rodent winds up falling prey to a hungry cat – completing the parasite’s life cycle, just as it has planned.

The upshot? Without Toxo, there would be a lot more rodents in the world (and a lot more hungry cats). Humans spend billions of dollars on rodent control every year. Meanwhile, we are getting an assist from a parasite – one that currently gets zero credit for its contributions to making human lives more hygienic and pleasant.

Need more evidence that we can’t live without parasites? Consider the nematomorph. This parasite lives as a long larval worm, folded up inside of terrestrial insects like crickets. But it lives as an adult in streams and ponds. If it emerges from its cricket host and finds itself on dry ground, it will immediately dry out and die. The nematomorph’s solution? It takes control of its host’s behavior, inducing in the cricket a deep desire to seek out water and drown itself. This is bad for the cricket but great for the nematomorph, which wriggles free into its freshwater home. The cricket? If it doesn’t drown, it gets eaten by a freshwater predator. In fact, there is an endangered species of trout in Japan that would almost certainly be extinct without nematomorphs. That’s because 60% of the calories the trout consume are terrestrial insects driven into the water by nematomorphs. The trout would starve without these parasites, making them allies to conservationists seeking to protect species from extinction.

Toxoplasma gondii and nematomorphs are merely two stops on the tour I lead through the netherworld. Power to the Parasites! introduces many more. It may cause you to fall in love with parasites, or it may not. But, whatever your opinion of these beasts, I know that once you read this book, you’ll move through the world thinking not just about the life that you can see, but also about the secret world of parasites that lies beneath.

Chelsea L. Wood is an associate professor in the School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences at the University of Washington. Her research program explores the ecology of parasites in our changing world. Power to the Parasites! is her first children’s book.