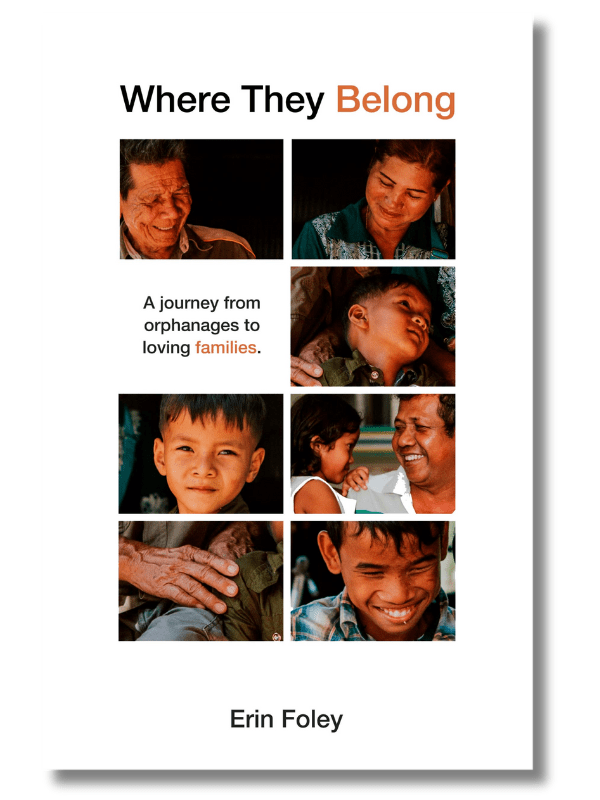

Where They Belong

by Erin Foley

Genre: Nonfiction / Adoption & Orphanages

ISBN: 9798891322967

Print Length: 388 pages

Publisher: Atmosphere Press

Reviewed by Elizabeth Reiser

An insightful exploration of the grim reality of traditional orphanage models and the need for family-based care

Erin Foley’s Where They Belong is a heartfelt and in-depth argument challenging the traditional model of orphanages. Using narratives from staff, volunteers, and children, in addition to her own experiences, Foley builds on these stories to showcase why family-based care is essential.

Set mostly in Cambodia starting in 1992, Where They Belong is told in three sections: “The Orphanage Years,” “The Children in Families Years,” and “Now What?” All three explore different aspects and repercussions of the orphanage model, providing heartbreaking stories and compelling arguments for support.

“With the pressure to fill beds and convince donors their money was going to orphaned children, they had inadvertently created orphans.”

In The Orphan Years, Foley relays one family’s journey (The Jones Family) of running an orphanage in southern Cambodia. This is the audience’s first introduction to Cathleen, the essential main character in this book, and this section makes it clear to the reader orphanages will not be romanticized. Instead, Foley showcases the corruption, abuse, and lack of care rampant in orphanages through conversations with workers and families.

She also sheds light on a focal point of the book: that many children in orphanages are not orphans, which is explored throughout each section. There is an especially revealing moment in this part where Foley discusses the orphanage emptying during Cambodian holidays when the children would leave to celebrate with their families. The children were returning to the orphanage happy to have been with their families but hungry due to a lack of resources, and it becomes clear to Cathleen that the orphanage system is not what is best for these children. How could money from the orphanage be better utilized for family social services instead? This is the heart of the issue Foley painstakingly addresses throughout and is one of the moments that propelled Cathleen forward in her quest to focus on the family units rather than the orphanages.

“If I were worried about offending people, CIF never would have started.”

The Orphan Years provides a solid foundation for part two, which focuses on the founding of CIF (Children in Families). Cathleen’s growing frustration is palpable and leads her to focus on a model to keep families in Cambodia together. This part of the book is quite dense, as it touches both on the emotional aspect of the work, as well as the intricacies behind starting an NGO. While the subject matter of this section is heavy, the reader cannot help but feel invested in CIF. It is also refreshing to see how Cathleen challenges herself to grow throughout the process. Her willingness to accept her weaknesses endears her to the audience. It becomes evident why Foley has chosen to focus on Cathleen so heavily.

As mentioned above, while the positive work done through CIF is inspiring, many of the stories shared in this section make for an emotional read. The outright exploitation of the most vulnerable population is highlighted here, and it is sure to upset even the most hardened of hearts. One of the most distressing examples is in the chapter “The Village Who Gave Away Their Kids,” where she details a village where every family put their children in a church orphanage. This was done because they were led to believe it was what God wanted for the children, for them to be taken away from their families. Using this, Foley emphasizes this effectively to showcase the importance of the work of CIF.

“You might find that the abandoned or orphaned children problem is linked to something bigger that needs addressing.”

The first two sections of the book focus on Cambodia, with the final section stressing the orphanage model as a global issue. The Now What? section explores what that means when it comes to family care, as well as reiterating the issue with orphanages. This final part of the book feels quite different from the rest. The essays and interviews with people in Thailand and Africa offer a unique view of what family means elsewhere, but it feels like being thrown into another book. However, that is not to say this section is without merit. It is fascinating to see the different cultural approaches, but the most impactful part of this section focuses on the negative aspects of volunteering with vulnerable children.

Foley contends that good intentions are not always best, and short-term volunteerism can lead to unexpected consequences. For instance, rather than teaching children to be cautious of strangers, they are expected to perform. It is another way Foley showcases how children in orphanages are exploited in the name of donations and fuels her argument for why it is so important to advocate instead for family-based care.

Combined, the three sections offer a full picture of a complicated issue. Foley’s use of the narrative structure helps to make the material accessible and less academic; the organization of the sections makes the vast amount of information manageable for the reader. It is clear how passionate Foley is about the subject and it does not read as sanctimonious. While there are clear religious overtones, she acknowledges the flaws of some of the Christian workers and how many have failed the people of the Cambodian community under the guise of Christianity.

It is not all heaviness in this book. Foley does a fantastic job revisiting different children and families throughout the book, and they often convene unexpectedly. These moments allow for joyful reprieve amid grim material. This is a necessary element, as it is hard to read about how orphanages are thought of as fundable by those exploiting them.

This is a well-executed book, even if dense at times.There is so much information to sift through, and the stories can blend, Christianity plays a large role in the book, and would likely appeal to a Christian audience interested in mission work, though it by no means feels exclusionary.

Where They Belong is an eye-opening look at the realities of orphanages. This is a must-read for anyone considering volunteering with, donating to, or adopting from any of the organizations discussed. The book will inspire conversation and make people think about the implications of some of these institutions.

“Now that we know better, let’s do better.”

Thank you for reading Elizabeth Reiser’s book review of Where They Belong by Erin Foley! If you liked what you read, please spend some more time with us at the links below.

The post Book Review: Where They Belong appeared first on Independent Book Review.