As longtime Corriere della Sera editor Mian writes, the 2,000-mile-long Volga river has long played a central role in Russians’ sense of national identity past. It does so today in Vladimir Putin’s world, where Russkiy mir is “not a philosophy, but a creed encompassing everything pertaining to Great Russia, where Orthodox Christianity, Fascist impulses, traditionalism, and a certain ‘Asiatic’ Soviet despotism coexist.” Traveling from town to town and city to city along the Volga, Mian, with photographer Cosmelli, teases out several related themes. One is the Russian people’s self-professed indifference to death. At the site of one vast World War II battle overshadowed by that of Stalingrad, a local historian reckons that the fight consumed “eighty-five tons of human flesh.” She asks, meaningfully, “Who else would give their lives for their country like that?” And that, she suggests, is what will restore Russian greatness, a motif sounded by young and old alike. Yet, Mian points out, Russian greatness seems a far distant possibility in so many places along the great river, where drugs, alcohol, despair, and roving Clockwork Orange–ish youth gangs rule, and where death is everywhere: not just the incalculable deaths in battle in Ukraine, but also death by vodka, car crashes (with death rates a staggering 60 times higher than in Britain), suicide, and industrial pollution in a heartland “where smokestacks, apartment blocks, daycares, warehouses, and churches exist together along the Volga in a suffocating cloud of ammonia.” It’s not a pretty picture, nor is the overall view of life under Putin’s rule, where dissidents, gay men and women, and minorities are oppressed, where right-wing Christianity dominates, and where, one priest confides, no one seems especially afraid of being incinerated in an atomic war.

Categories

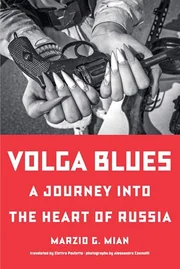

VOLGA BLUES